On Noise and Noisemaking

a critical essay by Matt Hart

On Noise and Noisemaking

Matt Hart

1.

When I listen to music (which is almost constantly—I’m listening to La Dispute’s “Stay Happy There” on repeat as I write this), I often find myself listening most intently to (and for) those sometimes deliberate, sometimes unintentional, out-of-control sounds and forces (glitches) that defiantly assert and call attention to themselves in contrast to the melodic and harmonic bedrock of the music: tape hiss, rhythmic unpredictability, weirdly bent or out-of-tune notes, dissonant clatter; bursts of pig-squealing, ear-splitting, headache-making feedback and distortion.... In other words, I find myself most interested in the noise, and noise is what I want to talk about in this essay. Eventually, here, my hope is to apply noise in/against the context of poetry as a way of exploding the poetic possibilities for meaning-making. I also want, in contrast to the more traditional notion of a poem as a kind of singing, to imagine a poem (at least potentially) as a kind of screaming, a kind of affecting racket. To do this, I need to spend some time up front, here, really digging into noise, what it is, how it works, and why it matters.

*

Unfortunately, that's not so easy to do, given the fact that noise is largely defined in terms of what it is not, i.e. music. Noise is a distraction from that which one is “supposed to be paying attention to.” As such it is also—at least initially—a shock to the system and sonically irrational, a musical irritant. Noise, unlike music—which is full of recognizable intervals, repetitions and patterns—is significantly insensible, the thing that music’s up against. Or, as my very smart friend, the poet, Jeffrey Sirkin put it to me in an email, “Music…signifies in terms of the noise it excludes.” How we listen to music—and what we enjoy about it—has a lot to do with its exclusion of the sounds (and sense) that would be a disruption to its formal and structural integrity and coherence.

2. Noise and Consciousness

"...noise is in fact the primary soundscape of our lives. It’s not always ear-destroying Ka-Blam! Sometimes it’s just static, or many conflicting sounds at once, such that it becomes difficult to distinguish one from another. . . ."

Noise, then, announces itself to our consciousness (at least immediately, initially speaking) as uncategorizable, unfiltered, unmediated sound/experience. It is the moment when we are stopped in our aural tracks and wonder what the fuck we just heard. The strange thing about it, however, is that noise is in fact the primary soundscape of our lives. It’s not always ear-destroying Ka-Blam! Sometimes it’s just static, or many conflicting sounds at once, such that it becomes difficult to distinguish one from another—was that a baby’s cry or a puppy’s, a rain shower or dry beans, Lady Gaga or Madonna or Miley Cyrus? Noise obliterates/undermines/subverts the logic of music.

What makes talking about noise even more difficult is that with regard to most of the noise we experience it's something we are largely hard-wired and socialized to ignore. How much noise have you heard today? Probably not a lot—your brain conveniently edited most of it out for you, so you could concentrate on things you actually really needed to listen to. Noise, then, is unnecessary sound—irrelevant and mostly meaningless in small doses, a thing to block out of our consciousness—a jackhammer whip-smacking pavement in the city, a woodpecker nailing my hangover to the wall, the babbling of the stupid little fucked-up brook of my migraine upon me never-ending.

And yet, we're all also aware of extreme (rather than everyday) noise and its potential dangers—noise can be the announcement of unspeakable carnage—a suicide bomb going off in a crowded market, the swirling roar of a tornado approaching—volcanic eruption, avalanche avalanche, the thunderbolts of Zeus! Still, some of the most extreme noises signify less than large scale catastrophe—the thud of a fist against a jaw, the look on the face of a child separated from her parents—and lost—in a crowd, even the cessation of breath, which is the quietest loud noise of all. “The slightest loss of attention leads to death” said Frank O’Hara. As artists we have to pay attention to everything around us. The noisy aspects of the world we ignore may be exactly the ones necessary for our aesthetic survival, revival, upheaval...

*

In contrast to noise, music is sound ordered in time; that is, sounds composed (improvised) and then made/played/performed to the exclusion of anything that would undermine their own coherence.

Noise is an unintended or deliberate sonic rupture or rapture in defiance of coherence—a force of destabilization, interference, breakage, wreckage, breakdown.

*

If music is “sound ordered in time,” noise is a kind of musickness: sound disordered and disorderly, an emergency of consciousness. The “barbaric yawp” of Walt Whitman, suddenly, Walt Wolfman. Noise in relation to music is pathological, a kind of musical illness—that if not brought under control, can overwhelm and destroy the body, both melody and meaning—and so also the suddenly not so eternal soul.

And similarly to the way an illness can be bacterial or viral, psychological or spiritual, noise in a poem (or other work of art) can be sonic or formal, conceptual or rhetorical. Ultimately, if we come to understand noise in any meaningful way, we do so in relation to the music—or as we shall see, the poetic bedrock—it’s up against. It is the abnormal, unhealthy, unclean, chaotic sounds that we evaluate against the normal, healthy, clean, ordered ones.

3. Noise and Contradiction

Speaking of sickness, the etymology of our English word “noise” comes from the Greek word nautia meaning “seasickness” of course. So “noise” shares a root with our English word “nausea”—a feeling of sickness, an imbalance of sorts (as it’s a form of motion sickness) that sometimes causes violent convulsive heaving—and the expulsion—expression of the contents of one’s stomach. To be nauseous—in noise—is to BE a little boat lost in a storm at sea. A noisy poem is a seasick poem. But as I’ve already noted, one person’s noise is another person’s symphony. What makes you sick might actually delight me. Etymology comes in waves. My metaphors mixing—which is itself a kind of noise.

*

To be a noise musician is to make music in full-throttle retreat from itself—a composition in contradiction, in conflict, in tension—one wedged between the more Apollinian forces of order and consonance and the more Dionysian forces of wildness and dissonance. A noise musician is a musical saboteur.

*

Thus, all the sound we encounter which is not ordered and which would be a disruption, interruption, or subversion of whatever music happens to be playing sweetly or blasting through the atmosphere of one's consciousness is noise. To borrow a phrase out of context from William Carlos Williams, noise is “the field of action” out of which music might emerge or be composed. It is wild sound—disorderly and surprising, disruptive and distracting, jarring and impactful.

Interestingly, wild sound and noise is more prevalent in recorded music than one might initially think besides the tape-hiss, etc., many musicians especially in the twentieth century (and continuing into the present) have found ways to subvert and disrupt more conventional pattern-making and note-ordering in the service of making new, never before heard (or never before attended to) “musicks” and sounds to push the boundaries of music, offending and expanding sensibilities along the way. One can hear this in the incessant repetitions of Steve Reich’s early minimalism, the atonal sound collisions of Charles Ives, the noisy silence of John Cage’s “4’33,” the free jazz horn blasts and leaping intervals of Ornette Coleman and Eric Dolphy, the spilled-out wrong-note-guitar solos of Black Flag, and Sonic Youth’s Feedback landscapes. Everybody has his or her own threshold, the place where music ends and noise begins. I’m interested in those blurry spots, the places where the song feels like it might fall apart at any second as a result of its own internal turbulence, the conflict between coherence and babble, between melody and squawk, between something which is pleasing to the ear and also potentially dangerous to it.

4. Poetry as Noisemaking

Now to finally bring this around in a big way to poetry: My sense is that for most of us the poems and other works of art that really grab our attention and hold it for the long haul (in the nick of time) first announce themselves as a kind of noise—a disruption of, against, and through the meadow of habitual being, the ordinary rhythms and music of our lives. These works are a surprise and at first significantly somewhat unrecognizable against the backdrop of our aesthetic expectations. Such works open our eyes our ears our hearts, and knock us loose from known/practical trajectories and easy logic, leaving us in awe and re-dis-oriented, changed and affected. Thus, at least at first, noisy poems are unremittingly strange. The noisy gesture in a poem and/or the noisy poem is a challenge to, and potentially an expansion of, poetic values and possibility in all the ways it unravels and sabotages, the expectations set up by the individual poem and also those set up by the art itself. Such poems make a dissonant squall. Their caterwaul and fame—the sounds they make in the world—are astonishing and often a challenge to good manners (craft) and traditional artistic values (good manners and decorum). Noisy art is—at least initially—an affront to the often skillfully arranged (that is, intended) consistency and order of our lives. Noise is not an intention. Noise demands attention.

*

"Noise remains disruptive, but in time becomes part of the idiosyncratic delight of a piece in the way that it surprises and cajoles us away from the implied expectations and the comfortable range of possible possibilities."

One thing to note is that noise in a poem isn’t necessarily, or only, a matter of the poem’s sonic architecture. When I speak of Noise in poetry—I’m thinking about those disruptive forces that come into a poem and make it wild (surprising or unpredictable, rackety or sloppy). Such forces undermine or clash with the poem’s formal, structural or conceptual integrity and trajectory—making it at least in part more a thing that one experiences than a thing one understands—a thing one is immersed in rather than a thing one apprehends—a thing that short-circuits listening (and other habitual ways of proceeding and perceiving) so we can hear/experience something. To make noise in a poem—to make a noisy poem—requires the subversion of its more traditional, recognizable poetic foundations, to pull the rug out from under it so that it might be made deliberately to fall (that is, fail) (in order to succeed). The trick of course is in finding ways to “insert sudden noise” HERE, that allows it to both call all attention to itself (if only briefly) and then to become part of the larger composition. Noise remains disruptive, but in time becomes part of the idiosyncratic delight of a piece in the way that it surprises and cajoles us away from the implied expectations and the comfortable range of possible possibilities. Noise is all the impossible ones, the ones that turn the poem’s world and maybe the world of poems upside down, inside out, O you turn me. Flowermouth, my dear. Exclamation Point! Underwear! Mr. President. AWK AWK AWK AWK! The leech. Shall we proceed? Proceed.

Think about air turbulence in flight. One minute you’re sitting back relaxing, enjoying the ride to Botswana, and the next you’re being bounced all over the sky, maybe even wondering if it and you are falling or falling fine. Noisy art is an art of sudden turbulence, of rough, even dangerous, skies.

*

Just to be clear—I'm thinking about noise as an aesthetic value—a thing of beauty, so also of difficulty. It’s the stuff that poets and other artists often deploy in the otherwise well-kept meadow of the meaningful word/world as a way to open new pathways of communication, demonstration, expression. Noise is a disruption—rupture and rapture, interference/static/distortion/dissonance—in an otherwise sensible signal. And in that sense, all poetry might be a kind of noise insofar as it sits in contrast to ordinary, practical usage and meaning.

The practical point of this entire essay, then, is in the notion that noise can be a useful modality to deploy in a poem, a way of getting out beyond what we know works—not to mention also our habits and (mostly shared) proclivities toward lyric expression or narrative progression and order. Noise can be beneficial in introducing a healthy dose of chaos and even deliberate sabotage into our work, a vehicle for getting out from under crafty-craftedness, so that we can lose control and find ourselves in the midst of new imaginative opportunities, generative risk-taking, and successful failure. With noise, we allow ourselves some communion with the unsayable, unsingable, unknown—that sweet spot where the limits of language press up against the boundlessness of experience.

5. The Difference Noise Makes

Etheridge Knight’s poem "Feeling Fucked Up" was one of the first poems I ever heard that really meant something to me, and it’s important to note that I heard it I the air—as a noise in the air—before I read it. It was the beginning of my interest in poetry—the conversion moment, the poem that for me, changed everything, made me want to be a poet. The first time I heard it, I couldn't believe it—“This is a poem,” I thought, hearing it blasted out loud in front of an audience. I was twenty years old and it wasn’t even Etheridge Knight reading it. It was a grad student named Bart Quinet, and there he was reading this punk rock cry of pain (at least that was my analog for it at the time) as a poem. And like many people in the audience, I was struck and struck again by its violence and soul, the noise it inflicted on my heart and my head, its cacophonous clattering rhymes, its consonance, assonance, and alliteration, straight out of the gate:

Lord she’s gone done left me done packed/up and split

and I with no way to make her

come back and everywhere the world is bare

bright bone white crystal sand glistens

dope death dead dying and jiving drove her away

The language literally comes out swinging, but its addressed at least rhetorically to/against the “Lord,” and the reason is “she’s gone.” We get this in the first three words of the poem. This is the poem’s occasion and its cry of pain, after which it elaborates on this cry, and erupts in an incredible tantrum, a litany of expletives, irreverence and fit throwing, venting and anguish, and it does so with such damaging, pounding, violent music, and rage that it’s difficult to remember that this is in fact a love poem and a prayer. The speaker takes responsibility for his loss, confesses, in fact, “Dope death dead dying and jiving drove her away.” Certainly, for a poet like Knight, who started writing poems in prison while serving a six year stint for armed robbery—(he was, in fact, a drugstore cowboy)—the notion of confessing one’s sins and taking responsibility for them is central to the poem’s affect. In the end, exhausted after all the curses he’s thrown around at everyone and everything from Marx to Jesus, from clouds to red ripe tomatoes, from Malcolm X to John Coltrane (both of whom were noisemakers in their own right and African Americans like Knight)—after all of that, the speaker breaks down, “All I want now is my woman back so my soul can sing.”

In “Feeling Fucked Up” the emotional situation, the torque of the feeling is out of control, a chaos of hurt, but the territory that becomes apparent when one finds one’s way through the poem’s noise-making and rupture is heartbreak and a desire to have again what one has lost. There’s something almost lovely (because it’s so recognizably human) about the force of the speaker’s feeling, and the music, with all its pot-and-pan banging, its “sheets of sound,” its fists through the drywall and wailing, is powerful. It’s a barrage of F-bombs, the language of the world (as opposed to what we traditionally think of as the language of poetry). “Feeling Fucked Up” isn’t all racket and screaming, it has a depth-charged soul in it that explodes; in its heart a light is on.

Noise-wise, since that’s what we’re after here, it’s important to note the extreme use of hard consonant sounds in the poem, and the intensity and relentlessness of its repetition— especially of the word “fuck” used as a curse and a command to heaven. I might note too that forward slash in splitting up the poem’s first line, “done packed/up and split,” as a sort noise within noise, a disruption in the syntax that allows us to pay attention to what’s on either side of it as both connected and separate, “Lord she gone done left done packed” and also “Lord she’s gone done left, up and split.” The pain necessitates the redundancy, and the redundancy works—feels real—because pain of this sort when it’s real is incessant. It throbs.

To be sure, the noise in “Feeling Fucked Up” is not only sonic, it’s emotional, a disturbance of the heart that erupts in the world, blotting out the rational mind for a time, before finally subsiding into exhaustion and quiet. Feeling fucked up is the blues—cursing and sobbing and wailing.

5. Noise vs. Noisy

Before going any further, I can imagine someone asking something along the lines of the following: “Okay, I see what you’re saying about the Etheridge Knight poem being noisy—and I can even extend the idea of noise to aspects of a poem that have nothing to do with its sonic architecture—but aren’t all poems noisy insofar as they’re up against the ordinary, practical, functional, non-aesthetic ways we use language? What precisely is the difference between a noisy poem and one that’s not noisy? Or, can you provide an example of a non-noisy poem?” Good questions. My answer might go something like this: Yes, every poem makes a noise (against the ordinary language it’s up against). Insofar as a poem is alive and teeming with life, it is also making a noise. But making a noise isn’t necessarily being noisy—disruptive, eruptive, dissonant, etc. Noisiness suggests a kind of endemic/internal agitation, a churning struggle at the edge of disharmoniousness (itself a noisy word). Thus, not every poem is noisy. What I’m interested in here are poems where noise is a primary mode and driving force—the animating principle of the poem—the thing that makes it tick as a part of its strategic or conceptual way of being in the world.

*

Noise knocks our teeth out, then pianos become the teeth.

*

Last summer I spent some time in a cabin in a wooded area near Lake Michigan. I couldn’t actually see the lake from where I was staying (for the trees!), but I could definitely hear it, its lapping constancy—waves of sound and the sound of waves, rolling in and breaking, rolling in and breaking. When I arrived the cabin’s kitchen sink was clogged—as it turned out with tree roots growing up into the pipes at the back of the cabin. The owner, not aware that tree roots were the problem, had hoped the sink would unclog itself but had poured a bottle of Draino into it before I arrived. Of course, Draino does nothing against tree roots, except maybe to give the tree a meth buzz, so after I called the cabin’s owner about the clogged sink two days in a row, he finally showed up on the third day with a bunch of tools and got to work. That day he spent 8AM to noon on his back on the kitchen floor in front of the sink twisting pipes. The rest of the afternoon, he spent out behind the house sawing the roots out.

Meanwhile, I was trying to write. But his wrench kept clanging against the galvanized metal plumbing, jarring me out of myself, stealing my attention (focus) and undermining my intentions. For some reason, the wrench against those pipes sounded like a wheezy B-flat minor chord, but it might just as well have been something resonant coughing, or something sickly breaking open, the disharmony of banging unmusical implements together for an unmusical purpose, a clog coming loose, gurgling out into the light. The pipes and the wrench were sound conductors both, and the cabin’s owner was the sound maker/unwitting composer, and noise-making concert grand master.

But these sounds weren’t music, of course. They were noise, an interruption, a distraction that I found myself immersed in, a sheet of racket that singled me out and pinned me to my hearing. Though to be fair, the landlord and his wrenches weren’t the only noise. I found myself distracted by a lot else in the woods too. At my feet the dog was panting. Her name is Daisy, a golden retriever in summer. Gusts of breeze kicked up and died off, seemingly from every direction at once. The trees’ leaves sputtered. A window fan purred. And in the distance, cars burned along at sixty miles an hour on the little road, Monroe, leading to Interstate 31, North and South. And not so far away some large vacation homes buzzed with life. Occasionally I could hear the voices of children ricocheting through the woods disconnected from their bodies, the sources of their sound, their radiant action, their radiance in action. Even in this quiet place all the sounds together made a racket—a noise and noises—and not unpleasant—even the wrenching pipes were more cottony than grating, more buttery than disorienting, more pipe organ than pipe problem—at least to my ear, which fixed on them. Clearly.

"Even in this quiet place all the sounds together made a racket—a noise and noises—and not unpleasant—even the wrenching pipes were more cottony than grating, more buttery than disorienting, more pipe organ than pipe problem..."

And yet, while I’ve already noted that these sounds taken all together or individually weren’t strictly speaking music, one could certainly attend to them as if they were. Even still, like most people I mostly heard the cabin sounds (as much as I may have enjoyed them) as a kind of aural interference, the disruption of an ideal (or ordinary) quiet, a distraction re-directing my attention to inattention, to something other than my writing—noise interfering with my thoughts about noise. Footnotes. Clouds in the sky. A window in a wall. We live in the midst and mist of bells and whistles, cries and squeals, snorts and calls. Sound, including noise, is not a backdrop; it’s immersive. It barrels into us, around us, through us. I don’t understand the physics exactly, but this isn’t really about that. There is a value in listening/attending to noise for its own sake, a mysterious world of possibilities and effects that defy conventional ways of paying attention, conventional structures and modes for meaning-making.

6. NOISE IN PARENTHESES

Mary Ruefle’s poem "White Buttons" from her latest book Trances of the Blast begins in the aftermath of a metaphorical blast, a literary explosion that leaves the speaker (a reader) in a state of shock,

Having been blown away

by a book

I am in the gutter

at the end of the street

in little pieces

like the alphabet

In other words, the speaker has been so moved or so shocked or so astonished by “a book” that it’s as if she’s been “blown away” by a great wind, a bomb blast, an unexpected, overpowering force. And here, at the beginning of the poem, she finds herself “in the gutter/at the end of the street/in little pieces/like the alphabet.” She is, in essence, at a loss for words—the emotional or intellectual chaos the book has stirred up in her has wrecked her world (devastatingly or joyfully, it’s hard to tell)—the noise of the book has disrupted her life so radically that there are no more words only letters of the alphabet. She is only letters of the alphabet, a voice blown to pieces in the gutter down low.

Weirdly, this is actually a desirable effect. Hopefully we’ve all had the experience of being blown away by a work of art, but hopefully we’ll never have the experience of being blown away.

The first six lines of the poem are immediately followed by one of our most common written disruptions, parentheses. In this case they arrive as a parenthetical address to the speaker’s mother, a note home to say essentially, “Dear Mom, I’m using the phrase “blown away” as a figure of speech. I am not really blasted to pieces of alphabet, the blast was not a suicide bomb, but a blast of consciousness brought about by a confrontation with art or knowledge.” A parenthetical is always a disruptive force, a noise in the train of thought, something which is being said and not said simultaneously. It is the ghost in the machine of the sentence—an aside, an elaboration, a tangent, a necessary clarification, but not one necessary enough to say straight out. A parenthetical is a landmine in a sentence. And while I’m sure that I don’t need to go into the fact that for most of us any conversation with our mothers is potentially explosive, it’s interesting here that after being blown away, the first “call” Ruefle’s speaker makes is to her mother. Notice too that the letters of the alphabet shift into “letters”—the kind you mail:

letters are not flesh

though there’s meaning in them

but not when they are mean

my letters to you were mean

I found them after you died

and read them and tore them up

and fed them to the wind

thank you for intruding

I love you now leave)

Thus, the direct address of the speaker to her deceased mother—this parenthetical noise as a letter to her mother in the poem—becomes a letter about the letters she wrote to her mother while her mother was still alive, and that the speaker found and re-read after her mother’s death. And what did she find when she re-read them? She found them, she admits, to be “mean,” so the poem’s parenthetical noise becomes a confession and a kind of apology, too. Interestingly, the speaker notes that after she re-read the letters she “tore them up/and fed them to the wind” so the letters and the speaker are currently in the same predicament “blown away… in little pieces.”

[And here the text of this talk breaks off—that is, my text breaks off… Interrupted by a clap of thunder or the phone, no doubt… or maybe I had to pee. I can’t remember… I will say, however, as disruptively as I must, that given the way “White Buttons” is parenthetically interrupted/disturbed three more times—after the first address to the speaker’s mother—with two addresses to her father and one to her sister—the poem is clearly a minefield of parenthetical explosions/detours—perhaps knocked loose by the book that blew the speaker away in the first place. I too am often taken somewhere (by something) when I read, not exactly against my will, but in spite of it. Noise begets noise(s). The poem is the result of a noise (the book). The poem is a noise (a musing, so a piece of music). And the noise of the poem is itself full of formal noise (the parenthetical addresses to the speaker’s mother, father and sister).]

7. THE ROLE OF NOISE IN ART/GRANDMA’S ASSHOLE

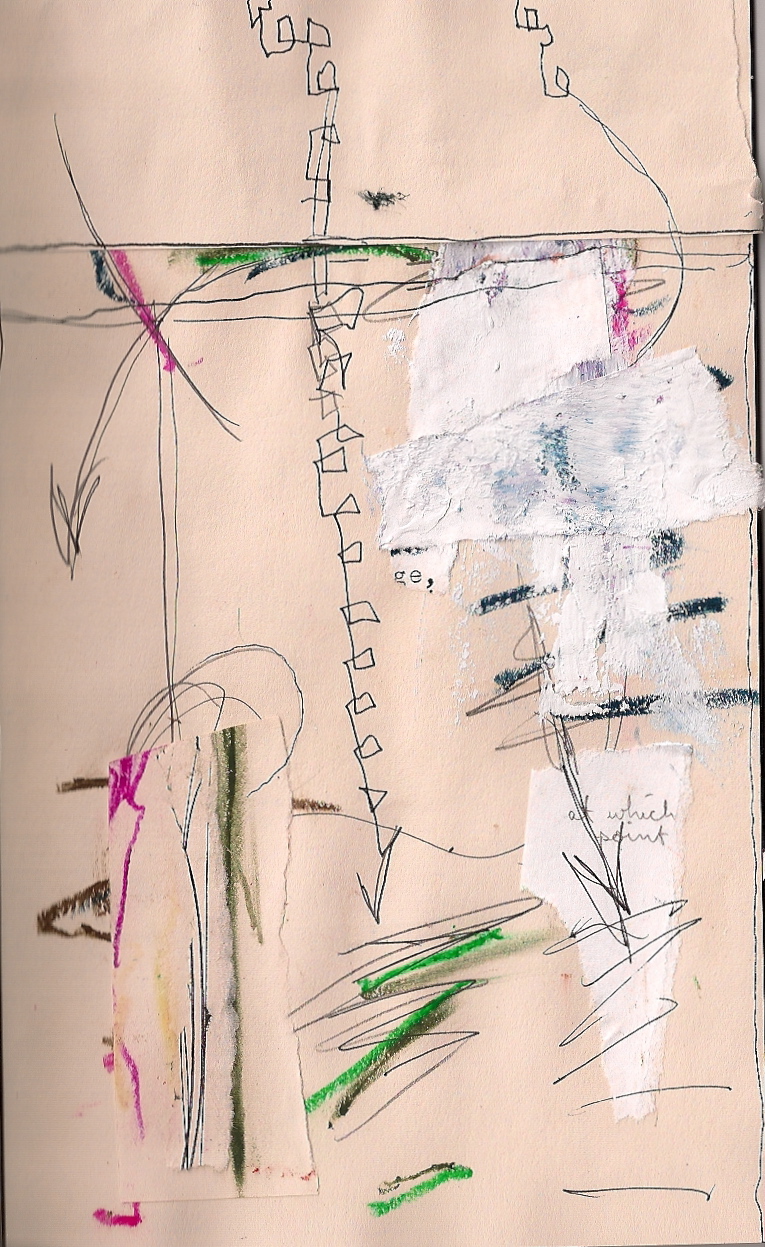

Noise can be extraneous, a parenthetical sound: an unwanted, unfiltered, or unnecessary presence. Usually this is an aural thing, but one might speak of visual noise as well: think of a riot, or a too loud shirt, a Jackson Pollock painting in the nude. What? It’s an intrusion on both sense and our senses, an interruption of conventional structures and logics.

*

Noise is to the mark as music is to the line.

*

And yet, cannot noise itself be meaningful in its disruptiveness, its rupture and rapture and defiance or ordinary sense, ordinary music? Is there a poetics of noisemaking? Are some poets wonderfully and/or alarmingly more noisemakers than singers?

I am excited by the ways poems often churn with tangents and static and awe-full-ness—i.e. ones that include noise as a matter of course—as a way of communicating the radiance and chaos of life that the poet, the poem, and poetry are immersed in and arise out of. Noise provides a way of saying what can’t be said (or sung or seen clearly) or it short-circuits saying altogether in favor of “metallic resonant glamour” (Gertrude Stein). Meaningful noise in a work of art provides necessary tensions and contradictory impulses that enliven, broaden and expand horizons in the sense that it forces us to pay attention differently than we would to something “well-wrought” (in the old modernist sense of perfection) and harmonious. Such noise, when it’s working well in a poem, creates ambiguity, more than vagueness, and augments the poetic transmission via a temporary diversion of attention from the primary mode of poetic expression, thus bringing the poem into more acute focus via contrast. Take this poem by Nick Demske:

Grandma's Asshole

I remember Grandma's asshole

simpler times and family

a piece of cinnamon toast and tea.

We'd have Christmas at the farmhouse

bundled up in handknit afghans

Grandma's asshole

and chamomile,

a story by the fire.

The World is different now, today.

Hustle and bustle

“No time to talk,” we say

and always going, going.

And that's when I need to come back home

our mountain cottage

snow in the forest

Grandma's asshole

the wood burning stove

and the kittens curled up beside it.

Where men are men

and the children have no cares.

Put another log on that fire, my friend.

Rest your weary bones with

your loved ones

a winters night

Grandma's asshole

we say a prayer

over homemade chicken soup

and for a single moment

everything is right.

In Nick Demske’s grandma’s asshole (and notice how the opening of this sentence is already a disruptive violation of decorum both upon your eardrum and to your mind’s eye…)—In Nick Demske’s “Grandma’s Asshole,” we find—oh no, I hope we don’t find anything… Are we actually looking…? Let me begin again. In Nick Demske’s “Grandma’s Asshole,” the very treacle-y, sentimental underpoem is nearly obliterated by the un-speakable, un-sing-able refrain “grandma’s asshole”—something no one wants to think about—calling attention to itself. Hidden it is nothing to think about. Out in the open, it’s complete chaos. In fact the only contexts where the phrase “grandma’s asshole” makes any sense are either medical (in which case, we’d be saying “rectum” rather than asshole) or pornographic (I hereby refuse to check to see if there’s actually a porn site called Grandma’s Asshole, but I’d be surprised if there isn’t).

What’s fascinating to me about this poem, however, is the way “grandma’s asshole” keeps disrupting the happy family at the heart of the poem—which is, if you take out the offending phrase—nearly a hallmark card to winter gatherings and quaint nostalgic yearning (thus, aesthetically offensive with or without the phrase). It’s a Thomas Kinkaid painting with a little Norman Rockwell thrown in to make it more than a landscape of purple-silver light.

Nick Demske's "Grandma's Asshole" sans "grandma's asshole"

Without grandma’s asshole, “everything is right.” But of course, it’s also totally wrong, as it presents something overly romanticized and idealized that it comes off as fake—a cheap set of Christmas decorations and lies about “simpler times and family”. The poem, without grandma’s asshole in it, is a terrible poem, and the phrase grandma’s asshole is a horrible phrase—both for what it evokes, points to—eww—and for its indelicate indecorousness. It’s not the kind of thing we bring up in polite conversation. Our assholes usually stay hidden for a reason, and grandma’s asshole in particular should remain under wraps. But even at the level of language alone, what could be more unpoetic than “grandma’s asshole”—where’s the truth and beauty in that?

And yet, when the sentimental underpoem and the phrase collide, something shocking occurs: Poetry. Now, I’m not here claiming that this is the greatest poem ever written (though I do like it a lot!), and there’s certainly a sense in which it reads like a kind of juvenile stunt—graffiti over the top of “The Night before Christmas” or “Over the river and through the woods to grandmother’s asshole we go…” Nevertheless, the effect is shocking, and the poem is a rather extreme demonstration of the sparks that fly when dictions collide and traditional expectation rubs up against the taboo, well-hidden, subconscious (out of sight out of mind) secret. Two things we as artists and polite human beings try and avoid come together in the light and make a horrifying and darkly humorous noise—one that embeds itself in our consciousness forever.

PS An interesting thing happens if we set aside the prankishness of Demske’s poem and take it entirely seriously. What if “grandma’s asshole” is the elephant in the room? Imagine that grandma has colorectal cancer. Imagine she’s dying. Imagine that she’s suffering. Imagine that she is the best grandmother anyone ever had—your grandmother—and even gathered round the fire, in the midst of trying to be normal with family and happiness, the only thing you or anyone can do is worry about her cancer, how her suffering and death will rip the family apart. And no matter how hard you try to distract yourself with anything other than grandmother’s illness—no matter how hard you pretend to engage in anything else—grandma’s asshole is the ever-present obsession, the thing that’s on everyone’s mind, but that no one wants to talk about. The interjection of “grandma’s asshole” in the poem—the unspeakable topic of its title—is that anxious inner voice, a sadness and preoccupation obliterating all other consideration (to misappropriate John Keats). Maybe the only way to “deal” psychologically with the problem is to make it as ridiculous as possible, to force oneself to laugh to keep from crying.

8. Noise as abundance

White noise: every frequency at once at the same volume. // Noise in art: Aesthetic simultaneity.

*

Overwhelming abundance = distortion

*

Another way of thinking about noise in poetry is in terms of chaotic abundance and plethora, the overwhelming profusion of things in the world—people, objects, sensations, and even language itself. Noisy poems of this variety seem almost to want to include everything, “to contain multitudes” as Walt Whitman might put it (and did in his very noisy, “Song of Myself.”) As a result these poems become distorted, the layering of details—of voices and objects and thoughts—piles up and piles on, creating a poem that’s primordial, in constant transformation, full of moving parts that don’t ordinarily fit together in any logical or coherent sense, but they erupt into new forms and new meaning through a kind of radical inclusion. And this results in poems (“Song of Myself” is a good example), which are difficult to navigate, since sometimes it feels like one is being bombarded by the poem more than it feels like a thing to be read. EVERYTHING is (or least seems) wildly, equally important, and meaning is matter accumulation rather than connection, of quantity more than aesthetic fineness and discrimination. Meaning is the wreckage of inclusion itself—of trying to stuff the world into a toybox.

*

James Schuyler’s "Hymn to Life" is a poem that I think really illustrates the kind accumulated noisiness I’m talking about, here, and also provides a good example of how such inclusiveness can itself become meaningful. The poem is a ten page, single stanza, nearly 400 line (383 by my count) ode to spring, beginning on the eve of spring and ending at the end of May, zigging and zagging through the blossomy effulgence of the season as it goes. In many ways, then, it’s exactly what the title sets us up to expect: A hymn—a song of praise—but not to God (a creator), but to Life (and death) (creation as god) (spring in its birth-song screaming) in all its fullness, even when and where that creation is hellish in overwhelming all-at-once uncontrollable nature:

The world is filled with music, and in between the music, silence

And varying the silence all sorts of sounds, natural and man made:

There goes a plane, some cars, geese that honk and, not here, but

Not so far away, a scream so rending that to hear it is to be

Never again the same. “Why this is hell.”

These lines from near the beginning of the poem set out for me one of its fundamental premises, namely “That the world is filled with music” and the poem is some more of it. But ironically so much music all played at the same time is cacophony, a riot of Paradise and thus, a sort of “hellishness.” It’s interesting that Schuyler has put “Why this is hell” in quotation marks in this passage—is it an interjection of a voice not the speaker’s or the intrusion of an inner voice belonging to the speaker? It’s hard to say which, because it’s both at the same time, but clearly it’s a vision of life that’s both inclusive and needs to be included, as one person’s music is another person’s noise. “Hymn to Life” doesn’t make distinctions about the value of the thoughts and experiences it presents as much as it acknowledges them as part of the nature of being, and since that’s what’s being celebrated, everything must be attended to, but not necessarily tended (or intended), not fenced, not forced into particular boundaries. It’s no coincidence of course that the poem takes place in spring, the season of rebirth—all those newborn screaming things, all those garish clashing blossoms—and the poem itself, to be sure, is some more of that—both music and screaming.

"Hymn to Life" is dense with personal detail, descriptive language, proper names, dialogue, not to mention also thoughts about writing, art, nature and living. The lines are so long that they almost turn into prose. One wonders if the fundamental unit is the fragment, or the sentence or the line in this poem, and that’s a part of its aesthetic of inclusion too, part of its own formal noise, as the poetic lines include both sentences and fragments. That said very few of the lines are end-stopped the poem is highly enjambed, creating a fluidity, a pile up of thought upon thought, language upon language, life upon life, the world upon the world in endless associations. In this way, the poem is long cascade of association, sound and image, but more than that it’s a cascade—a barrage, a flood, a waterfall—of words. It’s force is its accumulation via the mind in motion. To be associatively ordered is to let consciousness stream and spill out, allowing connections and disconnections to happen as they will or won’t.

Warmed and breeze cooled. This peace is full of sounds and

Movement. A couple passes jogging. A dog passes, barking

And running. My nose runs a little. Just a drip. Left over

From winter. How long ago it seems! All spring and summer stretch

Ahead, a roadway lined by roses and thunder. “It will be here

Before you know it.” These trees will then have leafed and

Showered down a harvest of yellow-brown. So far away, so

Near at hand. The sand runs through my fingers. The yellow

Daffodils have white corollas (speals?). The crocuses are gone,

I didn’t see them go. They were here, now they’re not. Instead

The forsythia ensnarls its flames, cool fire, pendent above the smoke

Of its brown branches. Beaches are near. It rains again: the screen

And window glass are pebbled by it.

“Hymn to Life” is a hymn to, and a celebration of, the minutia and backdrop of experience via language—especially the language of sights, sounds, and thoughts—that most people (though not poets) make it a habit to ignore. The poem reminds us that most of life is in fact noise, which we often do our best to organize, categorize, rationalize, and file away (if we can’t ignore it entirely), so as to be able to focus our time and attention on things that we care about and that matter to us personally. This sort of life noise/noise as life, life as noise, if we let it get the best of us, can be rather dangerous and even undermine one’s self-coherence. (To hear voices in the pathological sense is to hear voices that aren’t strictly speaking out there—the sounds don’t arrive from a source outside the body making waves. They are the result of the body making waves in its brain). Of course, “Hymn to Life” begs to differ with this pathological assessment, asking us to open ourselves up to the racket, “I hate fussing with nature and would like the world to be/All weeds,” Schuyler writes. The poem suggests a kind of mossy Eden. Paradise isn’t perfect. It’s overrun with weeds, unkempt, full-throttle. It’s Nature gone wild. And for human beings—obsessed as we are with dominating the natural world, cordoning it off, controlling and predicting it, manipulating it for our pleasure, convenience and financial gain to the point now almost of destroying it—it’s a terribly complicated thing. “Life, it seems, explains nothing about itself” Schuyler writes. Nature is, like the poem itself, its own explanation, and so asks us to pay full attention, to celebrate its booming plethora—wildness, wilderness and bewilderment, the weediness of Heaven, which is simultaneously hell.

9. What a Racket

*

Suddenly, all poetry is noise in so far as it resists the practical efficiencies and grammatical orderliness of ordinary language. As such, it is a challenge to—a disruption of—the ordinary, sensible ways of speaking and writing. To write a poem is to carve something out of the Vast or the Void of possibilities. If you don’t believe this is true, go through an entire day speaking only in terms of poetry, let’s say for example, rhyming couplets—especially when you place your order at Starbucks or the McDonald’s drive-through, and see if people don’t look at you funny, like you’re speaking another language.

Hi, I’d like to order a super large fry,

a filet-o-fish with cheese and a hot apple pie.

*

The most extreme example of noise in poetry—of noisy poetry—that I want to talk about comes from Carrie Lorig’s grand slaughterhouse of a Magic Helicopter Press chapbook, Nods. The book is divided into sections with the following titles that repeat in the same order: four times each in the course of the book, “SCATTERSTATE,” “CATTLEHURTER” and “It Can’t Be Love/It Must Be Love.” Additionally there are untitled sections, which precede each of these titled ones, and there’s one final untitled salvo at the end, a long blast that includes among other things nearly an entire page of the compounded word FLASHBLOOD repeated 179 times in a fully justified block with no spaces between each repetition. However, in the lower right hand corner of the page, this pattern is itself disrupted with a quote—a noise—from poet Edmund Jabes’ The Book of Questions, which reads, “There is no such thing (spoken or written) as a dialogue between persons.” A dialogue is a bit of writing—not between persons, but that produces the illusion/idea of persons in conversation.

Indeed, Lorig’s Nods—even as text—is not so much a dialogue, as it is an overwhelming, immersive experience. This is Poetry, not poems, writ large and with force. It is less a written thing to be read, than it is an exploded thing to be entered into (no doubt by writer and reader alike) (in fact, there are portions of this book, which are nearly unreadable in their run together celebratory excess):

m u s c l e c l o w n. hi. creaturehood. hi hi. my name is broad sides, bred sides for short.

the coughing i like is up here. i can get grey airs because i am like three minute song tall. crawl

towards me in your fun coat. under space, under inside the arms it is all skin and blur for combing

out. what you say to me, it makes shots of me. i don’t fuck much of the land, but green

and white spots oh, they b o o m on my eyemashes. when i lock up to this your face

of yours, i turn my face to eat the other way. i turn it to face

the ground. the ground is built to look up all things un-sky.

we stood grounding in the ground

and heard it go, POP. our skin is such caves. such young-ish caves.

a pain cattle, it is up to me. it lifts me up by the jaw and shakes me. it puts the whole head in

and hurls its c h e e k b o n e against me

i’m at this place

i’m at this place everyone splinters

(from CATTLEHURTER)

In Nods, one is touring the wreckage, the slaughterhouse of linguistic body parts and possibilities. It is a thing wholly in-control-out-of-control, managed via mismanagement, ordered via disruptive bursting. The sounds are lush and gorgeous, ridiculous and screamy, full of disclosure and mistaken identity, the need to both obscure and clarify. These are the storms of the sun, and the sounds of livestock being slaughtered, and the noises we make so in love with each other, so we follow the sounds (as Lorig follows the sounds) to a whole new universe: “i do my knees for a long time, and i lush out hard. i launch out hard because it frails good. like flows, like flower rodeos, i g r e w s o m e, I dark some and grope myself into full glow.”

The language is a textural wash—of paint brush stroke and/or the spurt of blood—it’s a bloodbath for sure, if any text ever was—of compounded (Frankensteined) words and phrases, run-on sentences and fragments, strange punctuation, deliberately inconsistent capitalization, exclamatory gestures, seizure after seizure, spasm after spasm. It is the language of calamity—disrupted at every level—a calamity of the word and of words, invented and reinvented over and over on the spot.

puptent,

whoafins, lunarsigh,

bonedome,

colorburn, paradepony,

soakbit tweezerolive, stemlace,

jamcloud, ripedrag

mangovault ironstyrofoam,

swarmgrid, dresssteam,

ghostpump, beautifulhinge,

mercypear,

popularwind, raidingstir, pocklocket,

kneegutter,

gasmauler, messyfuck, worksticker,

And this bit, from one of the untitled sections preceding one of the titled SCATTERSTATE sections in the middle of the book, goes on making up words and blurting-out for another two thirds of a page, finally ending with the line, “lifewound. mirrorroar. loveanimal ilove ido pleasebelievewarvolume”.

Perhaps the title of the work Nods, in its double-meaning, is an entry point. On the one hand, this poetry seems to nod a kind of acknowledgment (recognition) of its own churning whirlwind, its power to rip things a part while simultaneously putting them together. On the other hand, it is a woozy, drugged-out white noise, all consuming and hallucinatory, or as Lorig herself writes in one of the SCATTERSTATE sections:

it’s like dissecting the pain cattle and following them at the same time. this part is a body i’ve never heard of. this part is a body i’ve never heard an animal noise from. animals make noiseflowers. animals make noiseflowers better than any animal writing. animals make noises that eat spaces in the earth. animals make flowers that make noises in the earth. i said this book of animal writing in order to find the hurricane that speaks inside me. i eat the earth that hunches up into the soft spaces of hooves, and my body tightens and tightens with more parts.

(from SCATTERSTATE)

The repetition here of animal noise, of “animal” and “noise,” impresses upon us a sense of urgency, of drivenness and ecstasy, so dense and strange, one can only wallow in it or try and tear oneself away. “I AM A GIRL OF THE ELEGANT MIRE,” Lorig writes in one of the “This Can’t Be Love/This Must Be Love” sections. And “mire” seems a good word, the poetry is a struggle. The poetry is a thing one can get bogged down in, can be overwhelmed by—it’s totally and totalizing-ly, tantalizing-ly exhausting and exhaustive. Nods is full of patterns—even elegant ones—but it requires your full undivided attention, your full and unfailing patience, your unflinching empathy for large and small creatures, even other human beings, a willingness to engage the scream rather than the thesis with all one’s love.

10. POSTSCRIPT WITH SILENCE

Sonic wallflower vs. sonic wallpaper

*

noise canceling headphones

*

“Quiet is felt as disquiet, silence as unnatural, a seal to be broken, yet noise levels are rising inexorably across the globe, so sound is an irritant, a headache, inescapable, a physical assault on the senses, a threat to well-being, health and longevity.”—David Toop, Sinister Resonance p. 23

*

Silence is an absence of sound and that’s why silence is always haunted (Hautedness is the perceptible presence of an absence): No birds singing in the wilderness means something’s wrong, a predator’s afoot, a storm is blowing up. Silence can also be the ground upon—the habit or pattern against—which a noise (a tornado or the cry of a loon, the howl of a wolf in the distance) might announce very powerfully itself. In deep silence, a very small noise can have a massive effect. Silence is the beginning and end of noise, and so also the before and after of this essay. Silence is the beginning and end of noise, and so also the before and after of this essay/talk/scream into the void.

11. POSTSCRIPT IN SILENCE WITH HIDDEN NOISE

Silence can also be the ground upon—the habit or pattern against—which a noise (a tornado or the cry of a loon, the howl of a wolf in the distance) might announce very powerfully itself.

Recently, I had the pleasure of seeing a sculpture titled Versuchsreaktor (“test reactor”) by the contemporary German sculptor and installation artist Michael Sailstorfer. The composition of the sculpture is simple enough: a live microphone placed upside down in a block of concrete, such that the part of the mic one would sing or speak into is completely submerged, with the rest of the mic—its tail end—extending out of the concrete vertically. From there, the mic’s cable is connected to an amplifier, which broadcasts into the gallery space its very concrete predicament—that of being buried alive. The mic has been silenced, but it’s anything but silent. The sculpture sits on the gallery floor, picking up the vibrations (mediated by the concrete) of the room/building in which the art is housed—including the footsteps of visitors, the settling of the building, the ghostly (non)voices of the contemporary art world. The microphone has literally been placed below the surface of experience, and the sounds that come through it via the amplifier are subtle, otherworldly, new noises.

This monument (or is it a memorial?) to minimalist sculpture, Dadaist prank, and “silence as music” in the John Cage sense (where music is the sound in the air all around us) is both a curious “music box” and a kind of musical sabotage in favor of the usually imperceptible hum we’re immersed in (in this case, the bloodstream of the museum’s massive architecture). Sailstorfer in Versuchsreaktor has taken something useful and made it useless (in terms of its intended function)—which is one way of making a work of art. However, he’s also created, via the re-contextualization of the live microphone in concrete a new vehicle for unpacking, amplifying, and reimagining the very noisy silence all around us, demonstrating that sometimes by simply amplifying silence one comes face to face with a new kind of noise, the life coursing through life itself. The mic still picks up sounds, but they’re ones we wouldn’t ordinarily hear—or, alternately, they’re ones we would ordinarily hear, but not as we would ordinarily hear them. As Sailstorfer himself puts it in a description of the sculpture, “Noise means that something is in action, moving, breathing. Noise makes you experience time. Something making noise is alive.” In other words, sometimes determining whether a thing is living or dead is a matter of figuring out how to pay attention to its silence. Paradoxically, encasing a “live” microphone in a block of concrete doesn’t negate or silence life, it simply amplifies a different aspect of its (and our) liveliest possibilities. We don’t just hear the pulse and breath of the mic itself, but the vibration of the environment in which it waits to be released, the hum and gurgle of the life all around it. Even a thing in suspended animation is a thing in action, a thing nevertheless animate/d.

*

Whether or not one comes away from this essay writing noisy poems isn’t the point (though of course, I’m all for keeping one’s poetic options in motion and open). The point is how now do we pay attention to the noise and the silence, the musick and the message of being alive in a world that’s alive? I assert the value and living potential in the noise all around us, and in all the many ways that it’s already inscribed in our poems. I for one am not willing to miss out on any of it. I love the old familiar sounds, but there are so many more to be (at least temporarily) harnessed and (at least possibly) re-deployed as new noises, new music, new language, new life.

Matt Hart is the author of five books of poetry, most recently Sermons and Lectures Both Blank and Relentless (Typecast Publishing, 2012) and Debacle Debacle (H_NGM_N Books, 2013). A co-founder and the editor-in-chief of Forklift, Ohio: A Journal of Poetry, Cooking & Light Industrial Safety, he lives in Cincinnati where he teaches at the Art Academy of Cincinnati and plays in the band TRAVEL.