Questioning Taste, with Carl Phillips

Read this fresh interview with poet Carl Phillips, on Questioning Taste (September 2015) | Jam Tarts Magazine

Questioning Taste, with Carl Phillips

Interviewed September 22, 2015

Carl Phillips is Professor of English at Washington University in St. Louis, where he also teaches in the Creative Writing Program. He's written 13 books of poetry, including:

- Reconnaissance (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015)

- Silverchest (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013)

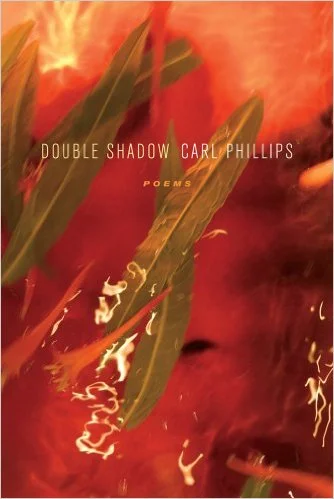

- Double Shadow (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012)

- Speak Low (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010)

- Quiver of Arrows: Selected Poems 1986-2006 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007)

- Riding Westward (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006)

- The Rest of Love (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2004)

- Rock Harbor (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002)

- The Tether (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001)

- Pastoral (Graywolf Press, 2000)

- From the Devotions (Graywolf Press, 1998)

- Cortége (Graywolf Press, 1995)

- In the Blood (Northeastern University Press, 1992)

His contribution to the "Art of" series by Graywolf Press, is The Art of Daring: Risk, Restlessness, Imagination (2014). He's also written a number of other essays over recent years, which can be found here and there; but while we wait for those to be collected, we have Coin of the Realm: Essays on the Art and Life of Poetry (Graywolf Press, 2004). And he's the translator of Sophocles’s Philoctetes (Oxford University Press, 2003).

I’d like my first question to you to be about questions. I’m not sure of another poet who uses the interrogative so well, so frequently and yet so quietly across his poems, especially in your more recent works (I’m thinking in particular of Double Shadow). Nor are your questions like those one finds in other poetry. Your questions have a will-of-the-wisp quality to them: They’re gentle and playful, like the wind—but also like the wind they can be wild or forceful, at times. Would you say that questions are a key element in your writing? And if so, what do you like about them? What don’t you like?

CP: I guess I think questions are among the most honest forms of expression, when it comes to the large issues in a life – desire, mortality, notions of the moral life, whatever. I don’t trust poems that make blanket pronouncements about such subjects, since these subjects are impossible to plumb entirely – and without that, how can we know we’ve gotten to something like a truth about a thing? So, yes, questions figure highly in my work, though I’d also say that any poem, for me, is an enactment of the questioning that comes with questing – which is how I think of a life of poetry, or really any meaningfully lived life, an ongoing quest for…for what, exactly?

In a similar spirit, you say in your foreword to Eduardo C. Corral's Slow Lightning that the poet’s “refusal to entirely trust authority wins [your] trust as a reader.” Can you tell us more about why you prefer to trust a writer who refuses to (entirely) trust authority? Couldn’t trusting authority be a risk in its own right—perhaps even more risky than mere rebellion, in some cases?

CP: Well, maybe I’d qualify things by saying that I don’t think there should ever be a blind trust in authority – there’s risk, and then there’s the element of calculation that distinguishes risk from gullibility or foolhardiness, maybe…On the other hand, yes, trusting authority can be, frankly, a turn-on, in the right circumstances – and there can be risk in that, sure…Depends, I suppose, on what you’re willing to give up, what you’ve got to lose, where you stand with respect to losing.

Speaking of losing: In The Art of Daring, you write “Who can say which is better, the glory of foliage or the truth of what’s left when the leaves fall away?” Here, and throughout this deft little book, you seem to suggest that human judgment is necessarily insufficient. But I wonder, is that your final verdict on judgment? Have you ever found judgment—or what you call elsewhere, “absolute closure”— to be successful in poetry that you’ve read?

CP: I think judgment is necessary, just in the course of getting through a life. You have to have an opinion, you have to have something by which to gauge your daily decisions. But I think judgment, like morality, needs to be flexible, able to adapt to how things inevitably change. And I think if the judgment, as expressed in a poem, is acknowledging that this is a judgment based on personally gathered data, rather than a big statement meant to cover all experience, then it can be successful. Even then, I don’t think such judgment has to amount – or should, even – to absolute closure. Somewhere in there, the awareness that judgment is mutable should provide the resonance that guards against the effect of absolute closure…the poems of Louise Gluck prove this is possible.

In your same book, and then again recently in your interview with NPR about your new book, you draw lines between restlessness and religion (or faith); and you raise a point about bending or breaking rules, testing boundaries we encounter. Yet you also seem to suggest that both artists and adherents must first know the rules, the forms and conventions they’re working within, against and toward—to be (in your words) “actively engaged in the machinery”—whether we’re talking about eternal salvation or literary tradition. Can you tell us a little about the rules that you follow and the rules you resist in your own writing practices? For example, would you say restlessness is a kind of golden rule for you?

CP: I don’t know if it’s a golden rule! It’s more like how I’m hardwired, for better and worse, nothing I can really control, let alone use as a generative device for poems, except insofar as I think the restlessness of imagination can lead us to thoughts that might become poems (in the way that Herbert’s God leaves humans restlessness as an element that will eventually lead them back to God’s breast, now that I think of it…). I don’t really have any rules that I follow, in terms of a writing practice. I write at random times, in varying conditions…If anything, I find that distracting myself is the way to get to a poem. I’m more likely to stumble into a good line while chopping tree limbs in the backyard, than if I were sitting at a desk trying to think of poem ideas.

Strangeness and beauty. I think I know how you’re going to answer, but I’d like to ask it anyway—do you think one requires the other? And why?

CP: I think beauty requires strangeness, because without that, it becomes just more of the same, so it wouldn’t stand out. I don’t think strangeness requires beauty, given how there are many strange things in the world that are unbeautiful. But then again, who is to say what beauty is, ultimately?

Through your years of teaching, how has your understanding of your own writing process changed? Have the people you taught also taught you something about your own taste?

CP: Hmm, two very different questions. To the second one, I’d say that my students have made me broaden my tastes, often enough – often a student will be a fan of work that I’ve never much cared for, but in the attempt to work with that student, I’ll return to the work, and begin to see things with greater appreciation. It doesn’t always work that way – sometimes I end up remembering why I never cared for the work in the first place…To the first question: I used to write at least once every week, usually on a Sunday, for the entire day. Very ritualistic. Over the years, I’ve become busier, between teaching and doing the usual poetry things, and then of course just living day to day – so I don’t have the time to have a writing ritual, which is why it’s become more sporadic. But that isn’t so much to do with my understanding of process, more just a matter of how life tends to shape things accordingly…

Can you tell us about something—some kind of art, piece of music or writing—that moves you today which hasn’t before been able to touch you? Some beautiful thing that you have eventually given into, perhaps?

CP: Do craft cocktails count? All of that movement had become trendy some time ago, but it only recently arrived in St. Louis. My initial impulse was to resist, just because I hate following the herd, and then if I am going to have liquor, I don’t want it adulterated and fancified…. But I’ve become quite a fan of The Lonely Hunter, Keep the Change, to name but two from a favorite haunt around here…and then there’s that grapefruit mint margarita that I just discovered…